Source: https://revistaidees.cat

Source: https://revistaidees.cat

European citizens see their voices being drowned out by those who benefit from commercial or geopolitical centres outside the continent. While democracies rely on an informed and thoughtful public opinion, citizens’ daily experience is now shaped by ‘feeds,’ resulting in the deregulation of information (1).

Things seem to become more worrying when we consider who produces and who distributes the information. In 2025, TikTok surpassed news websites as the main source of news for young people under the age of 25. At the same time, only 40% say they trust the news ‘most of the time’. Users – especially younger ones – are not abandoning the media because they are bored with current affairs, but because they do not see a place for themselves in the dominant discourse (4).

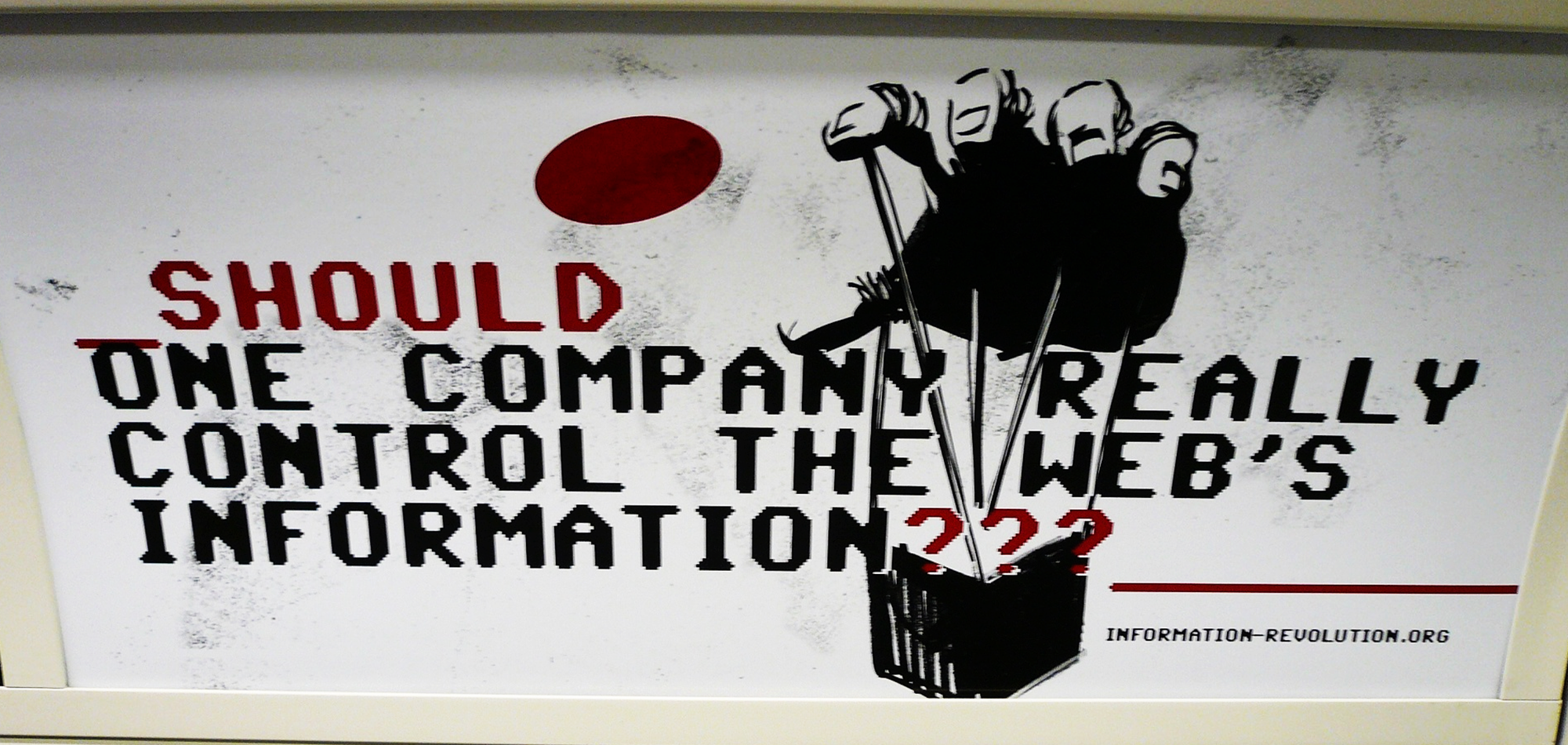

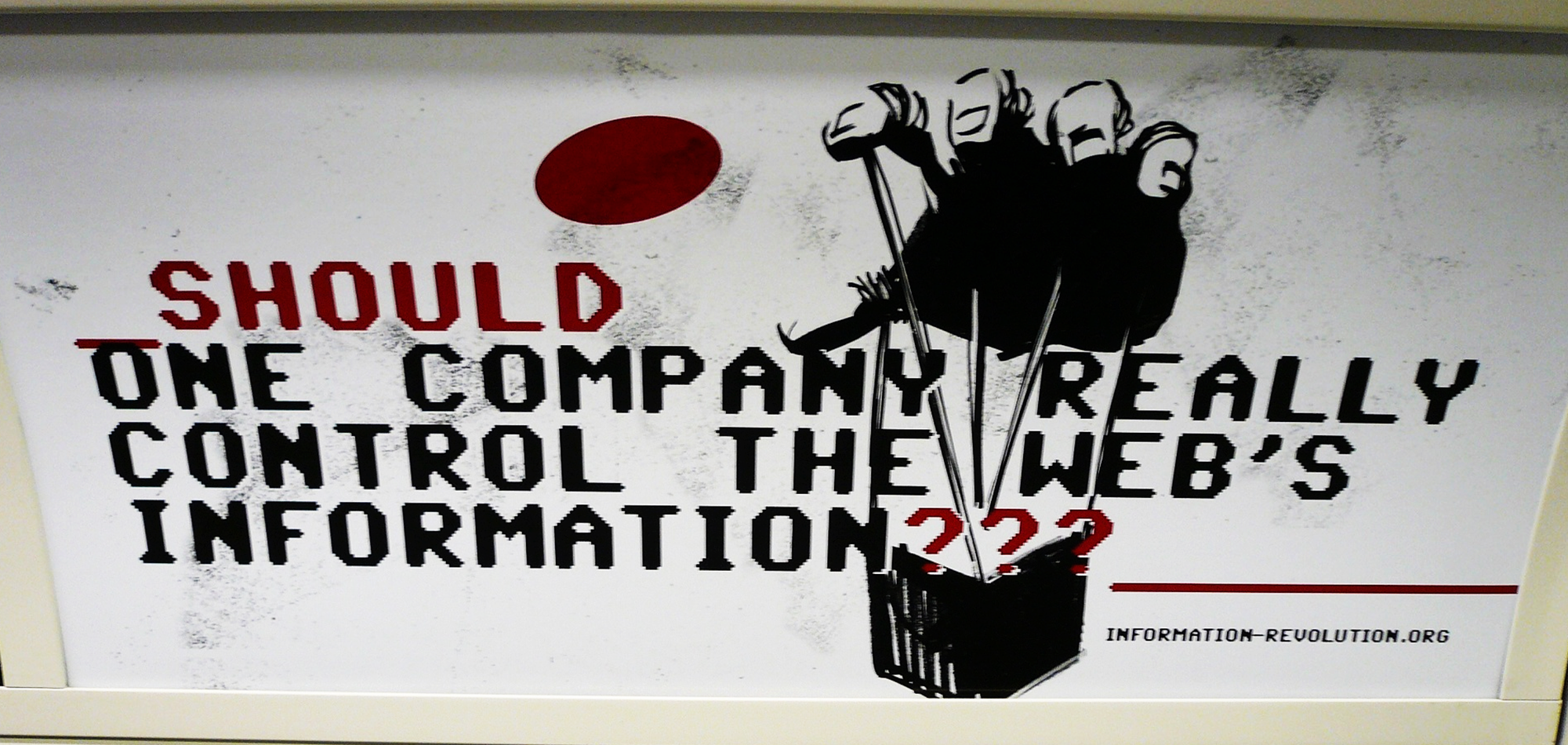

This disconnection is not neutral; it creates a political vacuum. The dominance of Big Tech, which promotes narratives based on engagement by creating increasingly extreme echo chambers, is combined with the weakening of public broadcasters. Platforms such as X (formerly Twitter) and YouTube amplify the voices that shout the loudest, not necessarily those that have a well-informed position. As a result, democratic debate is reduced to an exchange of shouts and memes, ultimately cultivating a culture instead of a temporary phenomenon (5).

And while Europe is trying to regulate, its tools are slow and fragmented. The legal progress of the DSA and DMA is not accompanied by corresponding investments in information infrastructure. We regulate platforms, but we do not create alternatives. We leave the field open to global players who are not accountable to European citizens, nor do they respect the democratic principles on which the Union is supposed to be based (3).

However, it should be noted that, unlike the American approach, which focuses on market freedom, Europe sees media pluralism as an institutional obligation and not simply the result of competition. The concept of internal pluralism, the existence of many voices within a public medium, is based on the idea that the state has an active role in ensuring participatory democracy, particularly through public information services and its regulatory framework. The public sphere, as shaped by European tradition, requires active policies that ensure access to quality and pluralistic information, regardless of geographical or social exclusion (8).

The passing of the Digital Services Act (DSA) and the Digital Markets Act (DMA) was a historic milestone in the effort to limit the power of Big Tech, but even the best legislation cannot change the fact that the digital public sphere belongs to others. Platforms should be seen as political structures that need more than just regulation and the corresponding restrictive infrastructure (1).

Strategic autonomy can’t just be about geopolitics or defence; European tools for communication, content sharing and information are needed to ensure freedom of speech and to avoid possible deregulation and fruitless fragmentation of public opinion. As Matthias Pfeffer points out, the issue is not to create a “European Facebook”, but a decentralised, multilingual, public information ecosystem accessible to all citizens in their national language (5).

The Council for the European Public Sphere has already proposed a digital platform that will bring together the news bulletins of EU public broadcasters and make them accessible to all citizens, with built-in automatic translation, accessibility and open source. The cost of this proposal is around €40 million per year, a negligible amount compared to the €27 billion that Europe already spends on public media (5).

Yet, even public infrastructure must be anchored in participatory legitimacy. The EU’s focus on tech sovereignty has failed to systematically integrate citizen participation. Regulatory action without democratic agency may replace foreign dominance with centralized, bureaucratic control. The risk is not just opacity, but the erosion of citizen trust in the governance of the digital sphere as a requirement of a democratic investment (7).

Information in Europe is not a neutral matter, as shown by the recently published Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2025. Younger generations are mainly informed by TikTok, Instagram and YouTube, with trust in traditional media declining dramatically. In Greece, less than 30% say they trust the news overall, with 18–24-year-olds clearly preferring social platforms to news websites (4).

This means that the platform, rather than the content itself, is becoming the main point of access to information. However, these platforms favour the promotion of emotionally charged, often false or misleading news, based on interaction rather than accuracy. This puts journalists in a difficult position, as they are forced into an opaque and constantly changing algorithmic mediation. This does not mean that journalism has lost its power, but that it operates in an environment where visibility depends less on the quality of content and more on how it is evaluated by platform criteria.

This new regime makes journalists dependent on form, with the risk that their work will be lost in the abundance of content if it does not adapt to the rhythms and priorities of Big Tech. Survival, not just influence, often depends on compatibility with the platform’s logic: catchy headlines, provocative thumbnails, trending hashtags. Journalistic independence thus translates into a battle for visibility in environments designed for other priorities – not for the public mission of informing. While access to quality information is foundational, it is not sufficient for democratic renewal. Europe’s current approach prioritizes sovereignty and competitiveness over participatory innovation. This imbalance risks reinforcing a technocratic governance model that sidelines citizens. A European platform must therefore go beyond content delivery, it must empower people as digital citizens, not passive users (7).

The discussion about a European public digital platform is the next logical step for democracy, a forum where citizens can be informed transparently, change perspectives and compare sources (5). Such a platform does not mean “Euro-propaganda”; it means that existing public content, including news bulletins, analyses and cultural programmes, will be made available in all EU languages, to all citizens, regardless of country, through automatic translation and interoperability (3). As Umberto Eco aptly put it “the language of Europe is translation.”

In this new digital environment, the criterion of pluralism is shifting from the diversity of sources to the diversity of user exposure. The concept of ‘exposure diversity’ is becoming increasingly important: democratic information no longer depends solely on how many voices there are, but on whether citizens actually come into contact with pluralistic content, especially content of public interest that is not reinforced by the attention mechanisms of platforms (8).

In order for the digital public sphere to once again become a space for meaningful participation, we need infrastructure that reflects the values of the EU, a common space for political and cultural coexistence (3).

This platform will not be a state broadcasting network or yet another social media outlet; it will be a multilingual public channel providing access to reliable, multinational information. Its design will be based on the principle of technical neutrality and political accountability. Essentially, it will not produce content, manipulate flows, or favour one narrative over another. It will draw on existing news production from public broadcasters, independent media and cultural institutions and make it accessible on a pan-European scale through automatic translation and thematic content linking (3).

Tests carried out in the context of projects such as the European Parliament’s STOA have shown that it is already legally, technically and linguistically feasible to link the daily news feeds of all European countries – either in real time or in curated thematic feeds – to a single platform, with a three-principle system, interoperability between different national operators and content types, open source code and the inclusion of AI translation infrastructure, and democratic governance, i.e. independent oversight, free from commercial pressures(5).

This proposal can redefine the right to information as provided for in Article 11 of the European Charter of Fundamental Rights — not simply as freedom of expression, but as access to pluralistic, evidence-based, transnational information regardless of national borders (5).

Europe does not have its own digital backbone; the basic platforms, cloud systems, and even information transmission standards remain imported from the US and China, making this gap a strategic weakness. When information depends on algorithms and platforms that operate on the basis of commercial success or geopolitical influence, digital sovereignty is not simply a desirable goal, it is a condition for survival (1).

The entire European narrative of democracy, accountability and fundamental rights is undermined when its pillars are under foreign ownership. For this reason, the rapporteurs propose – in addition to the strict enforcement of the Digital Services Act – the creation of a Digital Sovereignty Fund to finance European information infrastructure and alternatives to Big Tech models (1). At a cost of just €40 million per year, a fraction of the public media budget, this platform could become a daily democratic service for 440 million citizens (5).

However, no infrastructure, however technically innovative or politically noble its aims are, is guaranteed to succeed. The proposal for a European news platform, if not accompanied by social legitimacy and transparent governance, risks being perceived as top-down communication control, reproducing Euroscepticism and distrust in European institutions (4). An additional issue that needs to be considered is bureaucracy, where potential delays could drain the project of its necessary vitality, especially when competing with the immediate and interactive experience offered by private platforms (3). Finally, such an initiative cannot overlook the cultural specificities of Europe, nor can it approach multilingualism and polyphony as technical obstacles to be overcome. On the contrary, it must incorporate them creatively, otherwise it will run the risk of undermining what it seeks to protect: European pluralism (5); (3).

Do we want to continue to rely on opaque platforms that distort public dialogue, or invest in an infrastructure that expresses democratic values? Ultimately, the choice is rather simple: will we remain regulators in foreign territories, or will we become hosts in our own public space?

Do you have anything to add to this story? Any ideas for interviews or angles we should explore? Let us know if you’d like to write a follow-up, a counterpoint, or share a similar story.