After months of sending applications, tailoring CVs, and refreshing my inbox for replies that never came, I finally landed a job a month ago. The whole summer was spent chasing opportunities that seemed endlessly out of reach. This is a story that, unfortunately, isn’t mine alone. Across the European Union, countless young people face the same battle: degrees in hand, ambition intact, but doors to the job market stubbornly closed. Youth unemployment has become more than a personal frustration; it’s a collective crisis shaping the future of an entire generation.

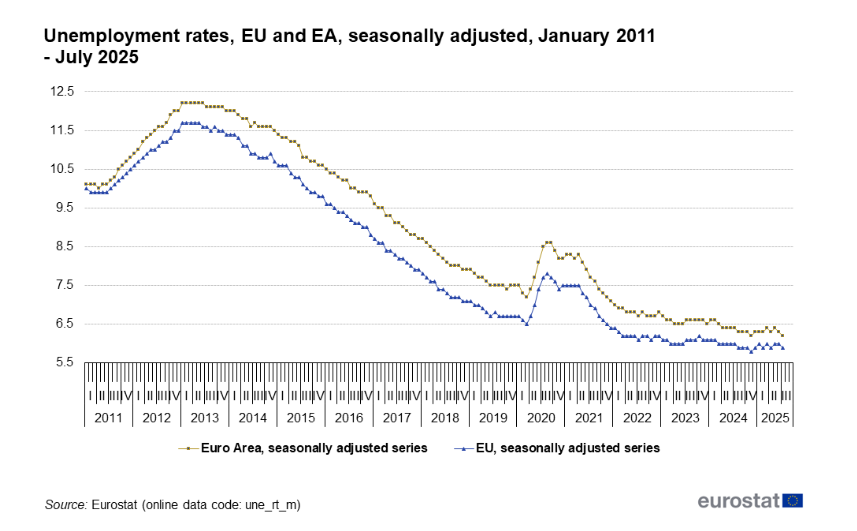

According to Eurostat, the EU unemployment rate managed to get to only 5.9% in July 2025, which is slightly less favorable than the one at the end of 2024, but much better compared to previous years.

This figure tells us exactly the ways in which the curve of unemployment rates has evolved throughout the years. We can notice a significant increase in this curve in between 2020 and 2022, with the peak being in the third trimester of 2020, in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic that changed certain aspects of life as we knew it before. Although the pandemic had a major impact on the unemployment rates worldwide, the effects were felt differently across the world and they were not uniform across countries or age groups.

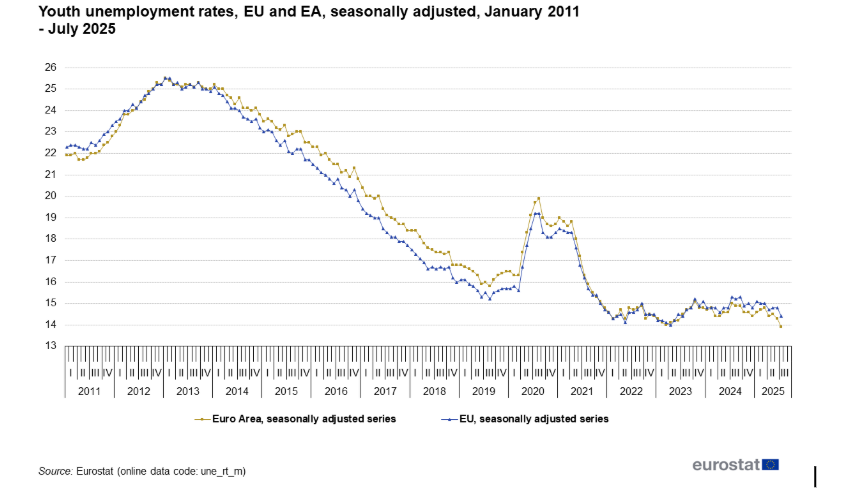

As of July 2025, a number of 2.801 million young people were found to be unemployed at EU level, with the unemployment rate being up to 14,4%. Although the numbers are lower than those registered in the previous month, when 14,8% of European youth citizens were unemployed, finding a place to work is still a complicated task for many of these citizens. But we also need to take into account that the EU pole for young people used here consists of people only up to 25 years.

What is actually happening around Europe and how are young people reacting to it?

In order to find out, I decided to speak with a few university students of recent university graduates from Romania, in order to find out more about the ways in which unemployment affects them on a personal level.

I asked them a few questions about their job search, the challenges they’ve faced, whether they felt prepared by their studies, and how external factors like COVID-19 may have influenced their plans. I was also curious to hear whether they felt hopeful about opportunities in the EU, and whether they’d consider working outside their field or even moving abroad to get started.

Here is what they have told me.

Giulia, 22

I have known from a very small age I wanted to do something with foreign languages and when I discovered what a translator does, I knew that was my call. Now after a Bachelor’s and a nearly complete Master’s in translation, I find myself battling with uncertainty regarding my future. In my country this profession or anything regarding to foreign languages, excluding teaching, is seen as useless, is underpaid or you can’t find a job without someone having to recommend you. For example, last summer I was searching for internships in the translation field and all I found were the ones in IT, management or sales and when I tried to contact places/institutions that worked with translation, I received no answer. But during my first year in my postgraduate degree, I discovered something that gave me a little hope. There are many traineeships that the EU offers for this field, which sparked a little bit more hope in my already crumbling perspective. I also want to address the fact that no university, at least in Romania, can guarantee you a real, stable job in our current society. You have to have some luck and a lot of patience to at least get you closer to where you want to be. And more so if you want to pursue a degree in humanities, its importance has been lowered, which, in my opinion, is in the detriment of our society.

Raluca, 23

When I finished my Bachelor degree, I had a period when I was constantly applying to jobs. I applied to every job I could, no matter the field or the expectations people had from that position. I graduated with a degree in the field of philology, so I thought that I have a series of skills as varied as possible. However, even though a lot of job ads claimed that they need strong communication skills, both verbal and written, every interview made it seem as if those skills are completely irrelevant to previous experience. It was really discouraging, I can tell you that. Now, I managed to find a job in the corporate field, even though that was never my first choice. But we’ll see how it goes.

Andreea, 23

I graduated this year from a highly regarded university, one that is well respected in my country. However, despite this, it is extremely difficult to find a job as a graduate with this degree. After finishing your studies, you can pursue a career in the public sector, but few positions are available through official competitions. In the private sector, the requirements for employment are often unrealistic, and opportunities are limited. Employers usually expect candidates to have outstanding grades and to be heavily involved in extracurricular activities related to the field. Yet these expectations are often unrealistic. Grades in university are given arbitrarily and do not always reflect the student’s actual knowledge. Moreover, the academic workload is so demanding that students rarely have time to participate in extracurricular activities.As a young graduate, it is very frustrating to try to meet all these requirements, knowing that the academic system itself does not provide the opportunities necessary to do so.

A common struggle?

The three testimonies reveal a common struggle faced by young graduates in the humanities: despite passion, dedication, and higher education, the transition from studies to stable employment is marked by uncertainty, lack of opportunities, and unrealistic expectations from employers. Translation, philology, or other humanities fields are undervalued in society, and even when students acquire strong transferable skills, these are often dismissed in favor of prior work experience. The job market tends to favor connections, luck, or unrelated fields such as corporate roles, while academic institutions provide little practical support for employment. As a result, many graduates experience frustration and disillusionment, feeling that their skills and efforts are underappreciated, while the societal devaluation of humanities further deepens their sense of instability about the future.

On the first search on Google, you can find a multitude of jobs that are advertised as for the youth. But the offers are not only what they seem.

Print screen taken on September 6th, showing websites that advertise jobs for young people. By simply searching “jobs for young people”, the Romanian youth can stumble upon a multitude of websites, based on their location, selected by the search engine.

How is Romania dealing with youth unemployment?

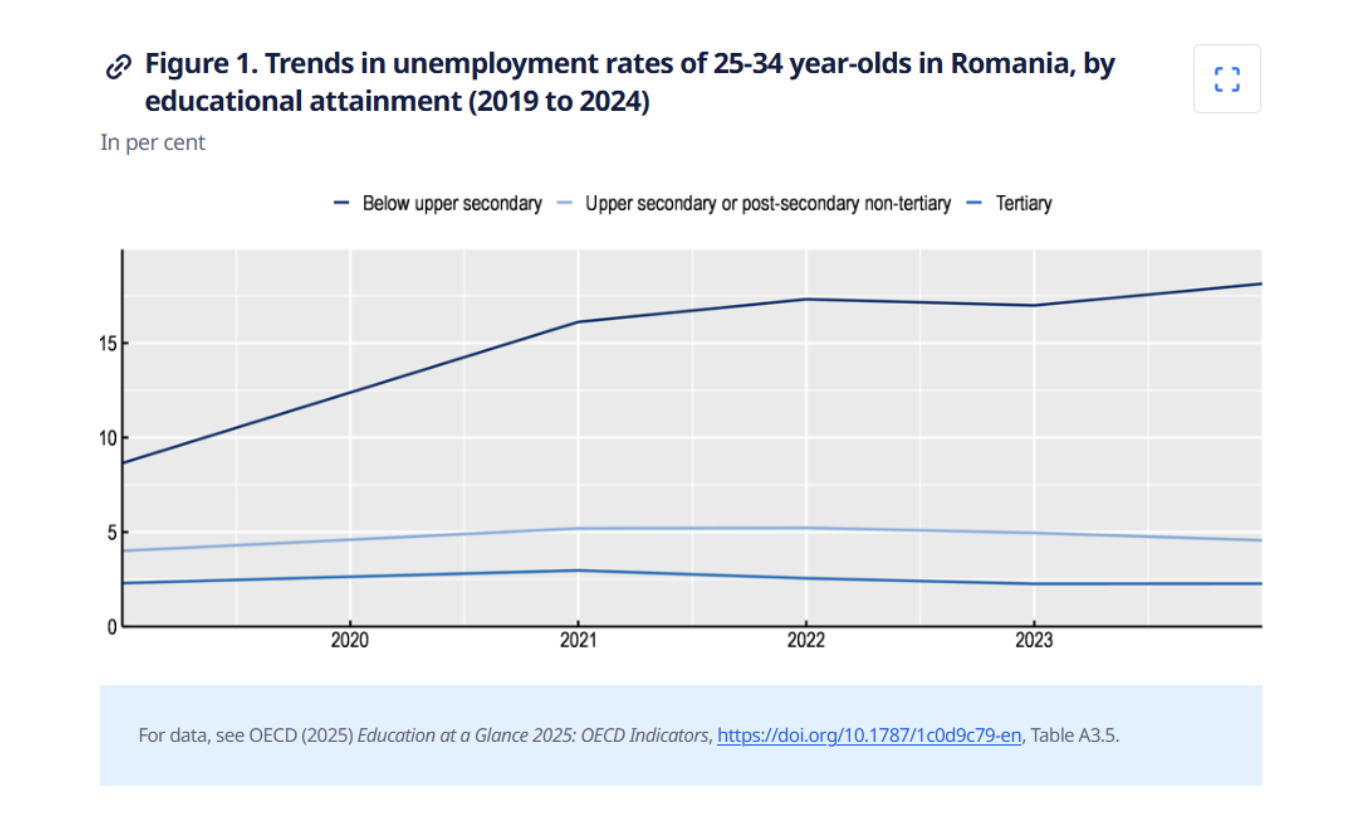

On September 9th, OECD released Education at a Glance 2025, a report which is, according to the organisation, “the authoritative source of information on the state of education worldwide”. According to the country note focused on Romania, the proportion of young people aged 18 to 24 who are not in employment, education, or training (NEETs) stands at 22%, significantly higher than the OECD average of 14%. Among those aged 25 to 34, the risk of unemployment or inactivity is particularly high, especially for individuals without an upper secondary education, where 18% are unemployed and 45% are outside the labor force. Regarding the impact that the educational system has on future young people who will enter the workforce, educational attainment significantly impacts employment prospects, reflecting broader OECD trends but with more pronounced challenges.

Therefore, while 42% of adults aged between 25 and 64 across OECD countries hold a tertiary qualification, only 19% do so in Romania, with a slightly higher share among younger adults aged 25–34 (which is equivalent to 23%), though this has declined from 26% in 2019. Despite a relatively modest wage premium for tertiary graduates, higher education in Romania remains closely linked to better job outcomes, where 92% of young adults with tertiary education are employed, compared to the OECD average of 87%.

However, many young Romanians face difficulties transitioning into work or further education, with 22% of those aged 18–24 classified as NEETs, well above the OECD average of 14%. Unemployment is particularly high among 25–34 year-olds without an upper secondary education, at 18.1%, compared to just 4.6% for those who completed upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education, and only 2.3% for tertiary graduates. And this goes to underscore the critical role of education in improving labor market outcomes.

The OECD also gives us this figure, which shows the evolution of youth unemployment rates in Romania, taking into account the level of education obtained.

Projections from the National Commission for Strategy and Forecast (CNSP) show that the slowdown in hiring across specific economic sectors, combined with challenges in integrating young people into the labor market during the early months of 2025, contributed to a rise in the ILO seasonally adjusted unemployment rate.

As a result, the unemployment forecast for 2025 was revised upward to 6.0%, compared to the 5.3% projected in the spring. The next projection (or the so-called autumn projection) is expected to come out in November and it should take into account the changes that took place in the first nine months of the year.

Until then, the National Employment Strategy 2021–2027 highlights youth unemployment as a key challenge, especially among NEETs (young people not in employment, education, or training). It aims to support their transition into the labor market through targeted measures like training, career guidance, and Youth Guarantee programs. The strategy also promotes youth entrepreneurship and better coordination between education and employment services.

On the same key, the National Youth Strategy 2024–2027 underscores that youth policies are a strategic priority, addressing challenges across education, employment, social inclusion, and entrepreneurship. The strategy presented in the file emphasizes an integrated, cross-sectoral approach involving various ministries and local authorities, supported by funding aligned with Romania’s Sustainable Development Goals, including ‘Decent Work’ and ‘Quality Education’, with a detailed action plan to guide implementation across institutions.

An important step was taken by the Ministry of Labor in May this year, when Simona Bucura-Oprescu, the Minister of Labor at that moment, claimed that the ministry would be investing, through ANOFM, over 63 million euros in projects to help around 51,000 young NEETs by offering training, counseling, and mentoring. Simona Bucura-Oprescu also emphasized that while youth unemployment has dropped, more work is needed to create quality jobs.

What happens now?

All in all, addressing unemployment, particularly among young people and those with lower educational attainment, remains a critical challenge for Romania. While progress has been made, targeted investments in education, training, and tailored labor market programs are essential to unlock the full potential of the country’s workforce. By strengthening cooperation between government, educational institutions, and the private sector, Romania can create more inclusive, sustainable employment opportunities that not only reduce unemployment but also foster long-term economic growth and social cohesion.

The future of Romania’s labor market depends on ensuring that no young person is left behind in this crucial transition from education to meaningful work.