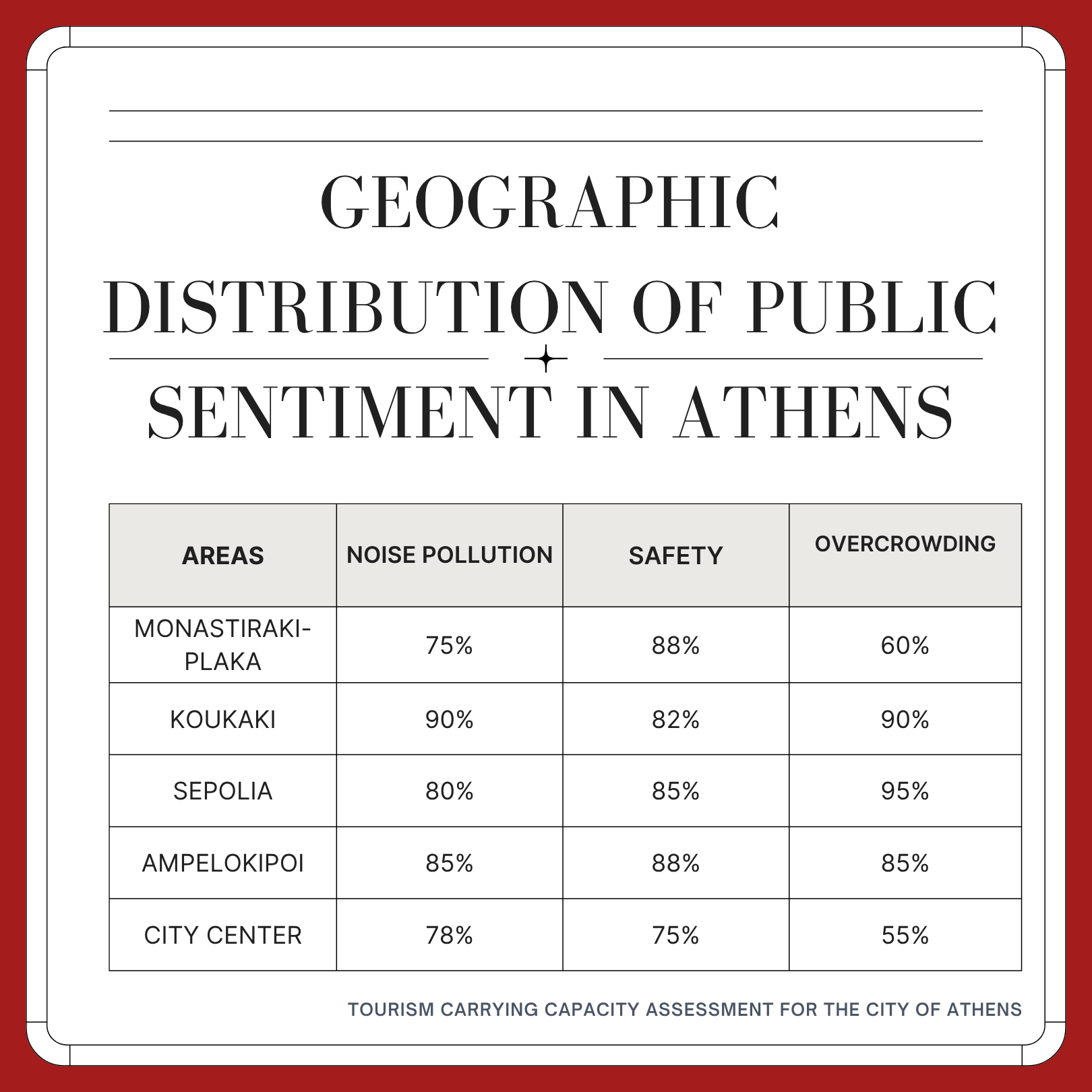

Credits: Table: Yorgos Karagiorgos

Data source: City of Athens, Results of the Carrying Capacity Study on Tourism in Athens, published on December 19, 2024, 16:00, City of Athens.

Presumably, if you were a nobleman in 17th-century Western Europe, you would want to test your instincts and experience the adventure of the south for educational reasons (sic). If, on the other hand, you were wealthy in the 19th century, you would probably take part in Thomas Cook’s (Thomas Cook was a 19th-century British pioneer of mass tourism, organizing the first affordable package tours across Europe) organised group excursions. And if we are talking about more recent years, after the Second World War you would have experienced the explosive growth of seaside tourism in the Mediterranean. Tourism has always been associated with the promise of escape and enjoyment. However, the transition from “travel as a privilege” to “travel as a right” gradually led to mass tourism, a globalised experience that today not only transforms local economies but also reshapes the very social and urban fabric of host cities (8).

British Gentlemen on a Grand Tour in Rome circa 1750 © incamerastock and Alamy Stock Photo.

In June 2025, thousands of residents in Barcelona, Majorca, Lisbon, Venice and other Mediterranean cities took to the streets to protest against the impact of overtourism on their lives: skyrocketing rents, loss of public space, disappearance of local businesses. With slogans such as ‘Your holiday, my misery,’ residents gave voice to a rage that had been simmering for years — a reaction not just to tourists, but mainly to a deregulated model of tourism that has excluded them from their own cities (2); (1); (4).

Cities like Barcelona, Lisbon, and destinations in Japan are seeing protests against overtourism, as residents push back over the economic and social strains caused by mass tourism pic.twitter.com/EJGGPaEHwq

— Reuters (@Reuters) August 15, 2025

Barcelona was once a model of ‘alternative tourism’ and sustainable urban development, but today it is at the heart of Mediterranean resistance to overtourism. On 15 June 2025, protesters flooded the streets of the Catalan capital, holding banners with slogans such as ‘Your tourism model is driving us away’ and ‘Barcelona is not for sale’. These demonstrations were part of a wider Europe-wide wave of protests against ‘touristification’, a term that now signifies the loss of public space, the displacement of residents from their homes, and the transformation of historic centres into theme parks for visitors (2); (1).

Under pressure from the protests, the local government responded institutionally: Mayor Ada Colau had previously imposed restrictions on short-term rentals, but the latest decisions were characterised by more drastic measures, with the abolition of all short-term tourist rental licences – such as those through Airbnb – until 2028, in an effort to return 10,000 apartments to long-term residential status. This measure was considered radical but necessary, as residents face unaffordable rent increases and the ongoing commercialisation of their urban space (3); (2). However, for many, this intervention seems long overdue, as everyday life already feels unbearable (1).

AP Photo/Pau Venteo

The situation in Spain is also illustrated by Leah Pattem’s emphatic account of how her neighbourhood in Lavapiés, Madrid, has been transformed from a community of immigrants and students into a field of fierce exploitation, with hotels charging €250 per night and old houses being offered as luxury short-term rentals. According to estimates, more than 15,000 illegal tourist apartments are registered in the Spanish capital alone (5).

Although the Spanish national government is trying to regulate rents and build social housing, the regional administration of Madrid, under the People’s Party, refuses to designate areas as ‘high-intensity zones,’ effectively blocking interventions. At the same time, recent urban planning regulations by the municipality allow entire buildings to be converted exclusively into tourist accommodation, deepening the housing crisis that also affects low- and middle-income visitors (5).

Athens was rarely included in discussions about overtourism in the Mediterranean, but it now ranks among an informal list of cities that are gradually losing their liveability. The increase in visitor arrivals in recent years has been accompanied by a proliferation of short-term rentals, a radical reshaping of the urban landscape and a silent but sweeping displacement of permanent residents. Elpida, a student at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, who has been living in Pagrati for the past three years, describes with dissatisfaction the changes she experiences on a daily basis:

“Rents are now unaffordable for a student, while the small shops that gave the neighbourhood its character have been replaced by concept stores and coffee shops full of tourists”.

The tourism boom in Athens – with subsidised branding campaigns, marketing strategies and incentives for investors – has been accompanied by an almost uncontrolled expansion of Airbnb, leading to a new phase of urban gentrification. Exarchia, Metaxourgeio, and even Koukaki – formerly ‘anti-establishment’ enclaves or run-down neighbourhoods – have been transformed into hot spots for digital nomads, real estate investors, and ‘experience tourists’ (7). All these factors have contributed to a rapid increase in rents, while public spaces are being aesthetically and functionally remodelled to meet the needs of visitors rather than residents.

Photo by Barbare Kacharava on Unsplash

Dimitris, an archaeologist and resident of Exarchia, touches on a less obvious but deeply fundamental dimension of the crisis:

“You know, when you see the neighbourhoods you’ve studied for years turning into tourist backdrops, it really hits you. It feels like the city’s layers, its history, are just being wiped away. Sure, the building facades are still there, mostly for some Instagram post, but behind them? There’s nothing left. Tourism’s sucking out the very thing that gave the city its soul—the messy,the beautiful diversity. Now it’s just rentals and visitors who come and go.”

Tourism in Athens took place without spatial planning and without social compensatory measures. The result is a reproduction of inequalities, with the tourism economy acting as a catalyst for class restructuring. At the same time, the social fabric is being torn apart, as permanent residents are leaving the historic centre and urban landmarks are being replaced by photogenic landmarks. Athens is in danger of being transformed from a vibrant capital into a “theatre” of its own identity, made for others, not for the people who built it (6).

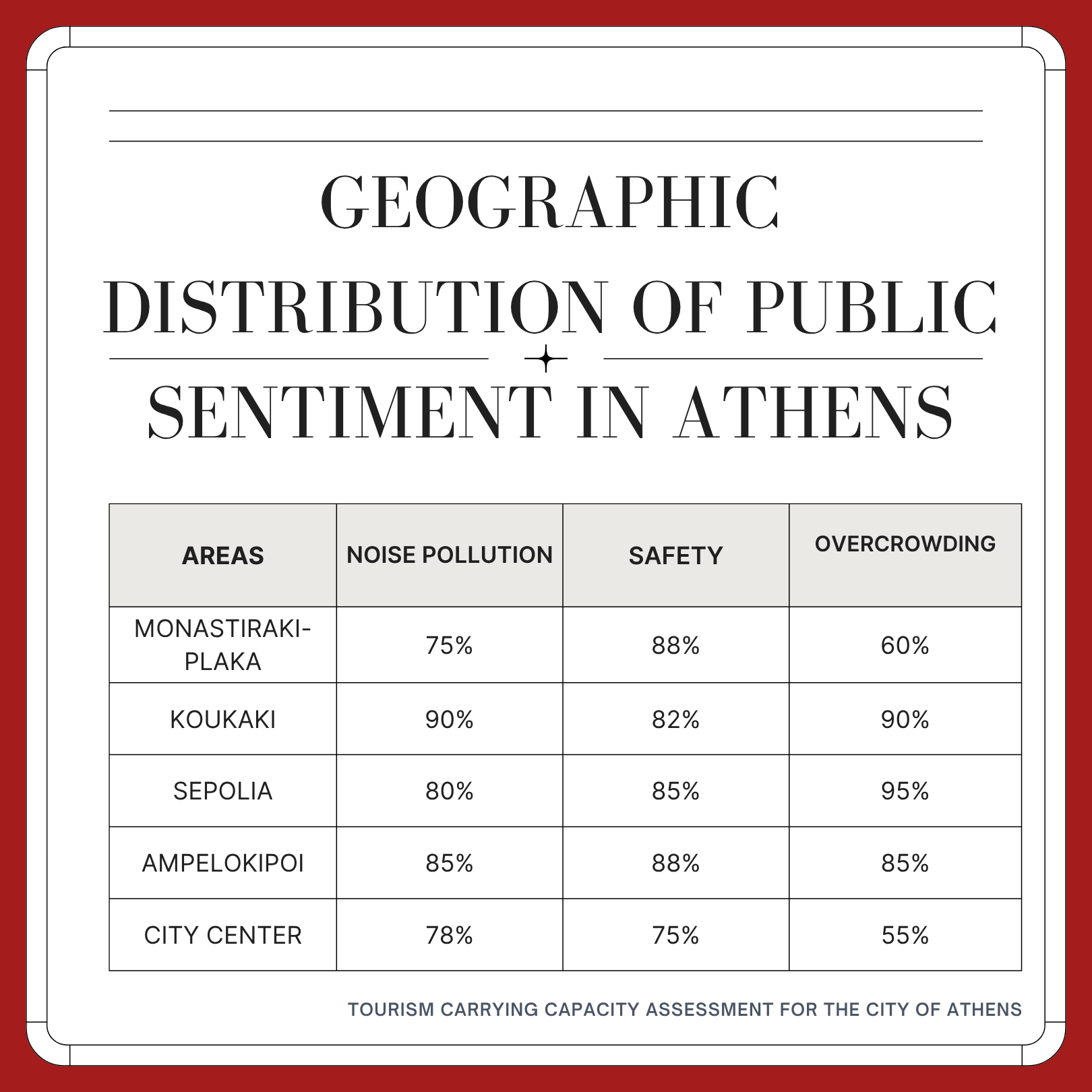

Credits: Table: Yorgos Karagiorgos

Data source: City of Athens, Results of the Carrying Capacity Study on Tourism in Athens, published on December 19, 2024, 16:00, City of Athens.

A new social divide is emerging in the streets, on balconies and in urban planning decisions, and that is the right to “live” versus the right to “visit”. The voices of residents rebelling against overtourism do not reject the concept of hospitality – they reject the model that distorts it. Tourism is not the enemy; it becomes the enemy when it is stripped of the political and institutional guarantees that would allow it to coexist with local communities (5); (6); (7).

The Mediterranean is called upon to rethink itself – not as an open all-inclusive resort, but as a place of cultural roots, everyday practices and historical continuity. The need for a new “social contract of hospitality” is more urgent than ever. Such a contract should include:

The tourism crisis is not just a question of “quantity” – it is primarily a question of policy quality. If the Mediterranean wants to remain a living place and not a theme park, then it must ensure that “visiting” does not negate “belonging”. The irony is that the history of tourism itself has generally been characterised as a tool for knowledge, intercultural exchange and social mobility. Today, however, this historical thread seems to have been violently severed, with the transformation of tourism from a means of contact to an experience export industry bringing about a new colonisation of the space. Re-education is needed, not only for travellers, but also for the policies that define where the visitor’s gaze stops and where the resident’s everyday life begins.

If the nobles of the North once toured the European South as part of the Grand Tour to acquire cultural capital, today’s mass tourism travellers are not so different: they collect moments and images, turning neighbourhoods into consumable backdrops. Just as the South became an object of appropriation back then, so today it is being emptied of local content, the visitor’s gaze does not meet the other, but bypasses them. Everyday practices, social interactions, even the tensions of coexistence, evaporate to make way for a sterile representation of the “authentic”. The tourist experience is transformed into cultural memorabilia, leaving behind silence. If we do not reinvent the meaning of hospitality as a relationship, not as a product then the very concept of place is lost.

Photo by Arno Senoner on Unsplash

Do you have anything to add to this story? Any ideas for interviews or angles we should explore? Let us know if you’d like to write a follow-up, a counterpoint, or share a similar story.