Based on EMI report, June 2025 [Zofia Grosse]

In June this year, a report was published by European Movement International (EMI) in cooperation with the research company Savanta. The study surveyed 3,504 adult respondents from seven EU member states: Poland, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and Romania. Its main goal was to capture citizens’ opinions on the state of democracy, the functioning of EU institutions, and defense cooperation in Europe. While the results contain elements of optimism, they are dominated by signals of deeply rooted disappointment and weakening trust in democratic institutional mechanisms.

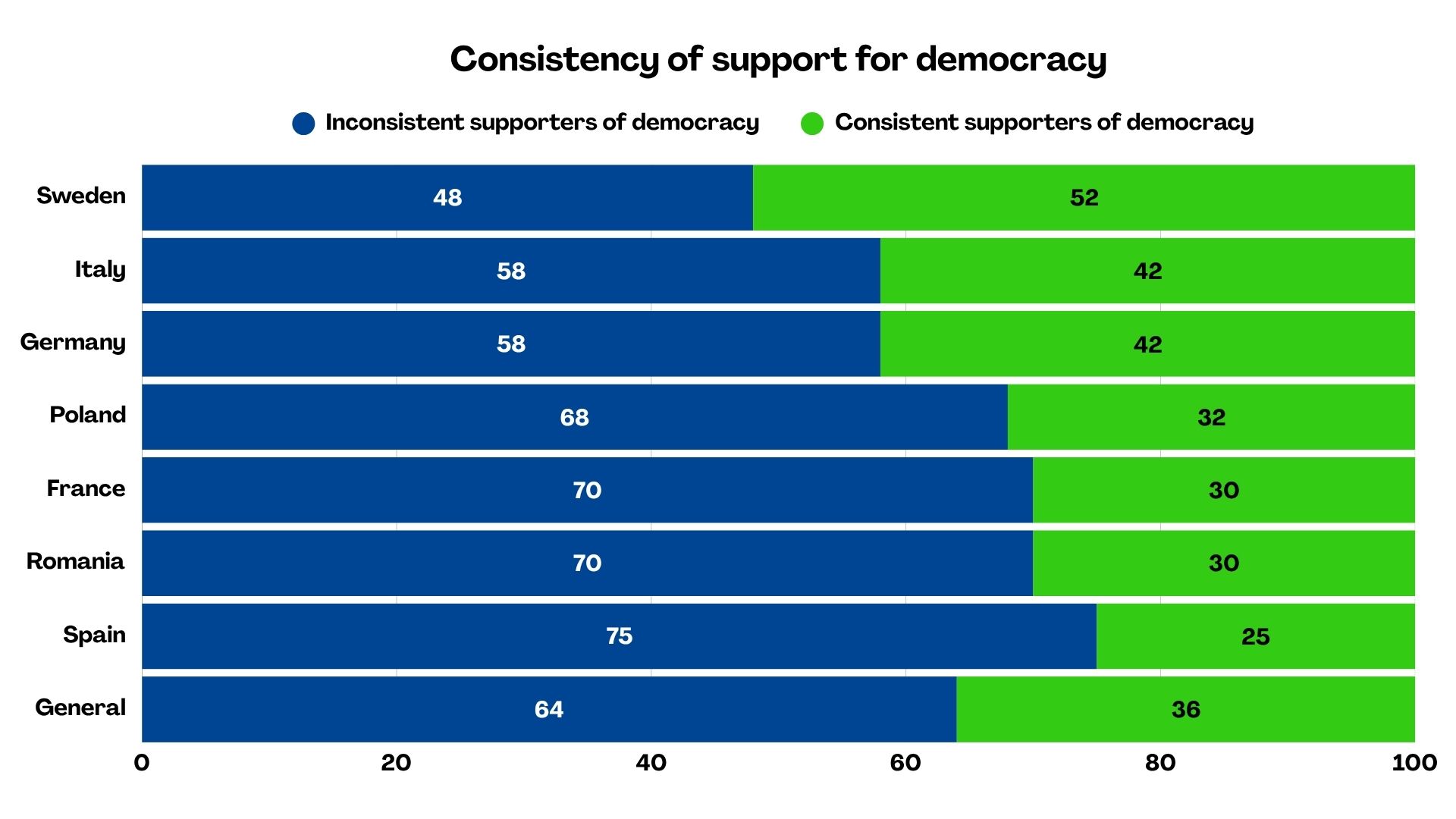

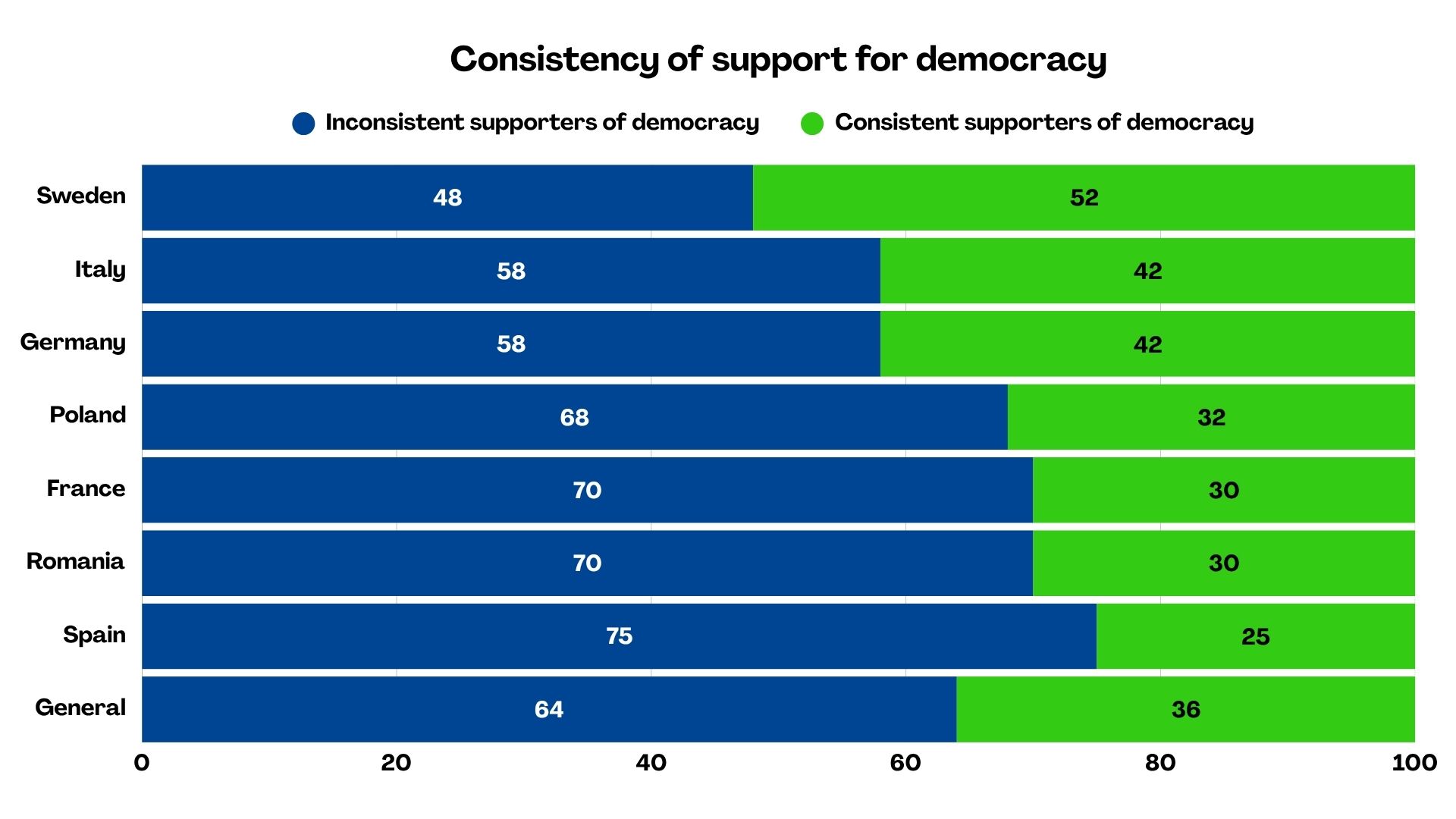

The study shows that only 36% of respondents can be classified as consistent supporters of democracy—people who believe both in the value of the right to vote and in the need for effective mechanisms to control power. A full 64% display inconsistent attitudes: some lean toward support for strong leadership by a single person, while others condition their support for democracy on immediate benefits. Although the decline in trust in democracy is not a new phenomenon, its current scale is cause for justified concern.

“Low levels of consistent support for democracy are truly alarming. However, this does not mean that citizens are anti-democratic. They are simply disappointed, disempowered, and frustrated—and that is fertile ground for authoritarianism,” notes Petros Fassoulas, Secretary General of EMI.

Poland’s position among other countries in this context is ambiguous. Only 32% of respondents can be considered consistent supporters of democracy—this result is higher than in Spain but lower than in Germany, Italy, or Sweden, which emerges as a leader in attachment to democratic values. A deep social divide is particularly visible here: on one side, a strong declared attachment to the principles of democracy and European integration; on the other, growing skepticism toward the effectiveness of democratic institutions and their ability to influence citizens’ lives in practice.

The trust index in EU institutions is also relatively low—only 14% of Poles declare greater trust in EU institutions than in national ones, while 44% trust their own government more. Just 34% of respondents in Poland believe that EU membership has had a positive impact on the country as a whole, which is the lowest result among all the analyzed countries. By comparison, this figure reaches 71% in France and 65% in Italy.

Based on EMI report, June 2025 [Zofia Grosse]

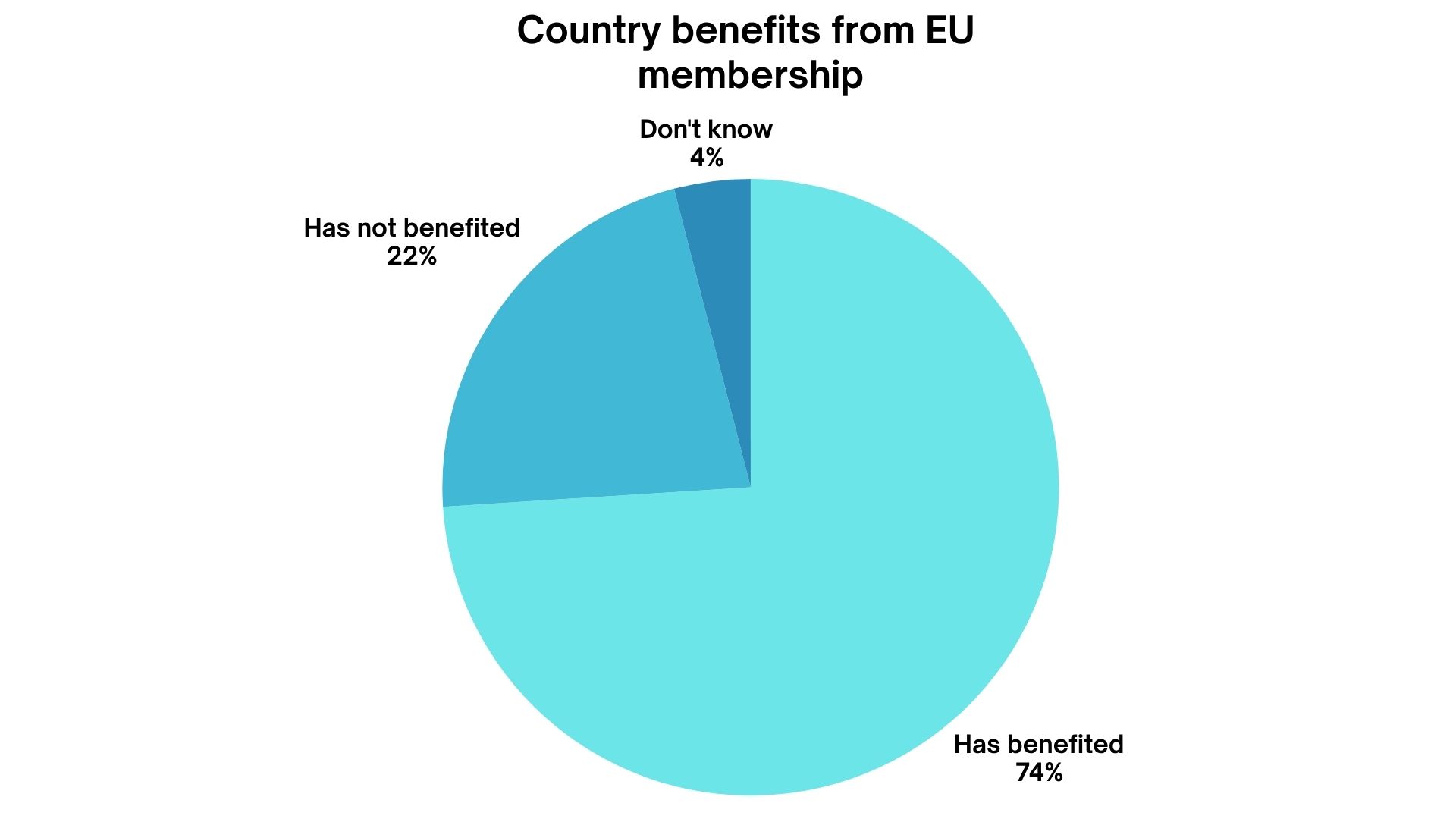

This somewhat pessimistic picture is complemented by a broader context presented in this year’s latest Eurobarometer survey, whose results show a much more optimistic view among EU citizens—including Poles—regarding the European Union and its institutions. According to this survey, as many as 74% of EU citizens believe their country benefits from EU membership—the highest figure in the history of measurements conducted since 1983. Despite the results indicated in the EMI report, Poland also ranks high in this regard, contradicting the simple thesis of deep Euroscepticism. Moreover, 89% of respondents across the EU believe that greater unity between member states is key to effectively addressing global challenges—this opinion is shared by over 75% of citizens in each member state, including Poland.

Eurobarometer data also show that Europeans—including Poles—increasingly view the European Parliament as an institution that should play a greater role in the Union’s political life. They also expect the EU to have more competencies and resources to counter crises. Citizens appreciate the practical aspects of integration—68% of Poles point to freedom of travel as the greatest advantage of membership, 62% value the sense of security, and over half see it as an opportunity for better educational and professional prospects abroad.

Despite the optimistic tone, Eurobarometer also reveals social concerns—especially related to the economic situation, inflation, and rising living costs. More than half of Europeans fear a decline in their living standards, which—although not directly related to their assessment of democracy—may influence an overall sense of political alienation, symptoms of which are also visible in the EMI study.

Based on Eurobarometr report, winter 2025 [Zofia Grosse]

Against this backdrop, an interesting phenomenon emerges, which could be called a European paradox: despite weakening attachment to formal liberal democratic mechanisms, support grows for joint actions at the EU level—especially in the context of defense and combating disinformation. More than half of respondents support the creation of a joint action plan regarding the war in Ukraine and the establishment of a European army.

Even greater support—reaching 66%—was given to EU initiatives aimed at combating disinformation campaigns. In Poland, 54% of respondents support the idea of a common army, and 53% want closer cooperation in light of the war on the eastern border. Although this might seem contradictory to rising nationalism and limited trust in EU institutions, it rather indicates a search for a new model of European solidarity and security that would respond to an increasingly unstable world.

The results of both studies—EMI and Eurobarometer—not so much contradict each other as complement one another, painting a fuller and more complex picture of contemporary social moods in the European Union. This image is at once realistic and full of tension: on the one hand, citizens are losing faith in the institutional efficacy of democracy and feel fatigued by its formula; on the other, they recognize concrete benefits arising from integration and do not give up on the idea of community.

Poland, as a country at a political and identity crossroads, is a particularly vivid example. On one hand, there is a clear need to redefine its place in Europe and rethink the model of democracy; on the other, expectations toward Europe as a space of solidarity, development, and security remain strong.

All this leads to the conclusion that the future of democracy in Europe—and in Poland—does not depend solely on political elites. The final direction will be set by the citizens themselves, their sense of agency, trust in institutions, and belief that their voice truly matters.

Do you have anything to add to this story? Any ideas for interviews or angles we should explore? Let us know if you’d like to write a follow-up, a counterpoint, or share a similar story.