Europe’s Gates Close: Greece as a Testing Ground for a New Migration Policy

Photo: Yorgos Karagiorgos / Kara Tepe-Mavrovouni, April 2024

From Solidarity to Surveillance

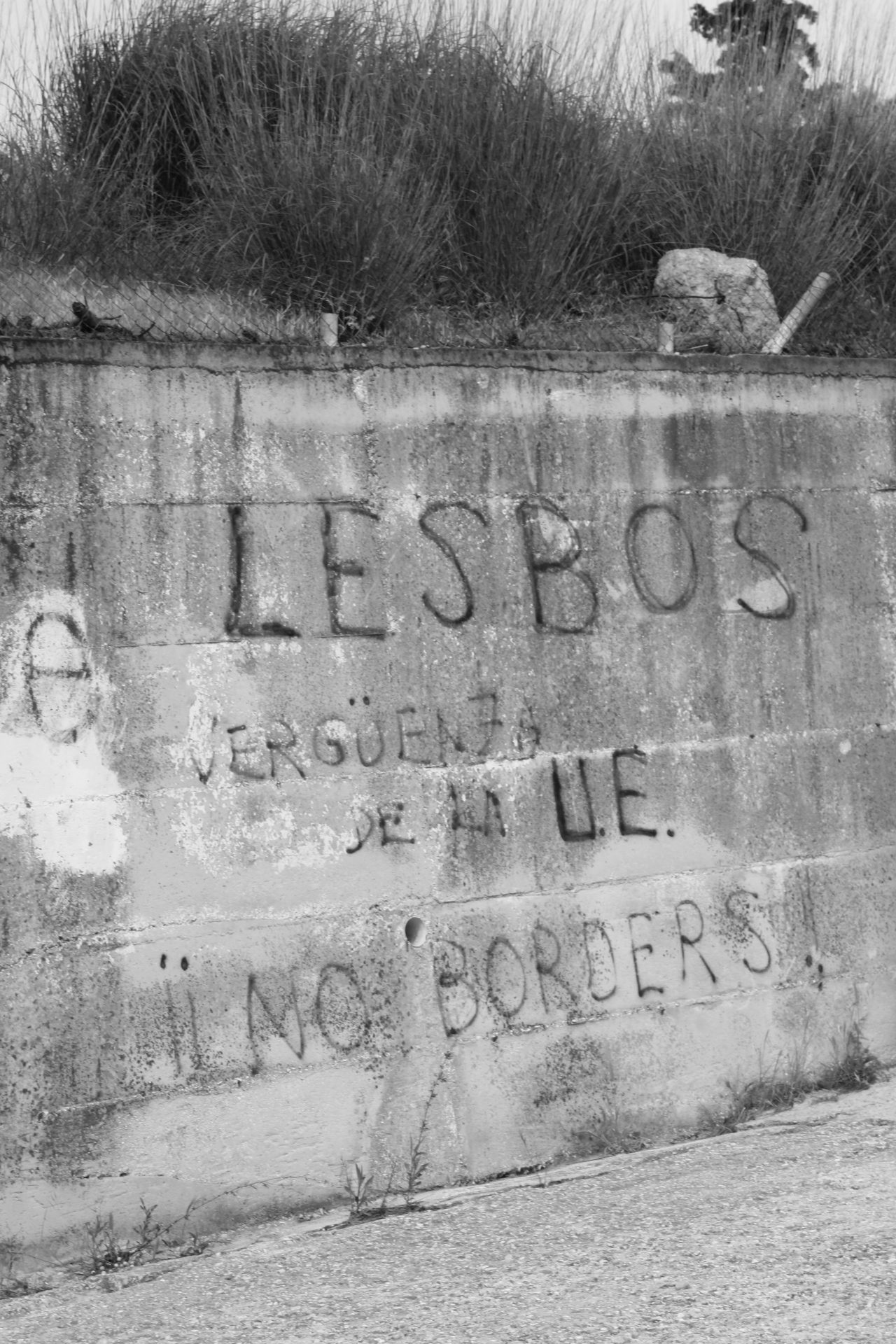

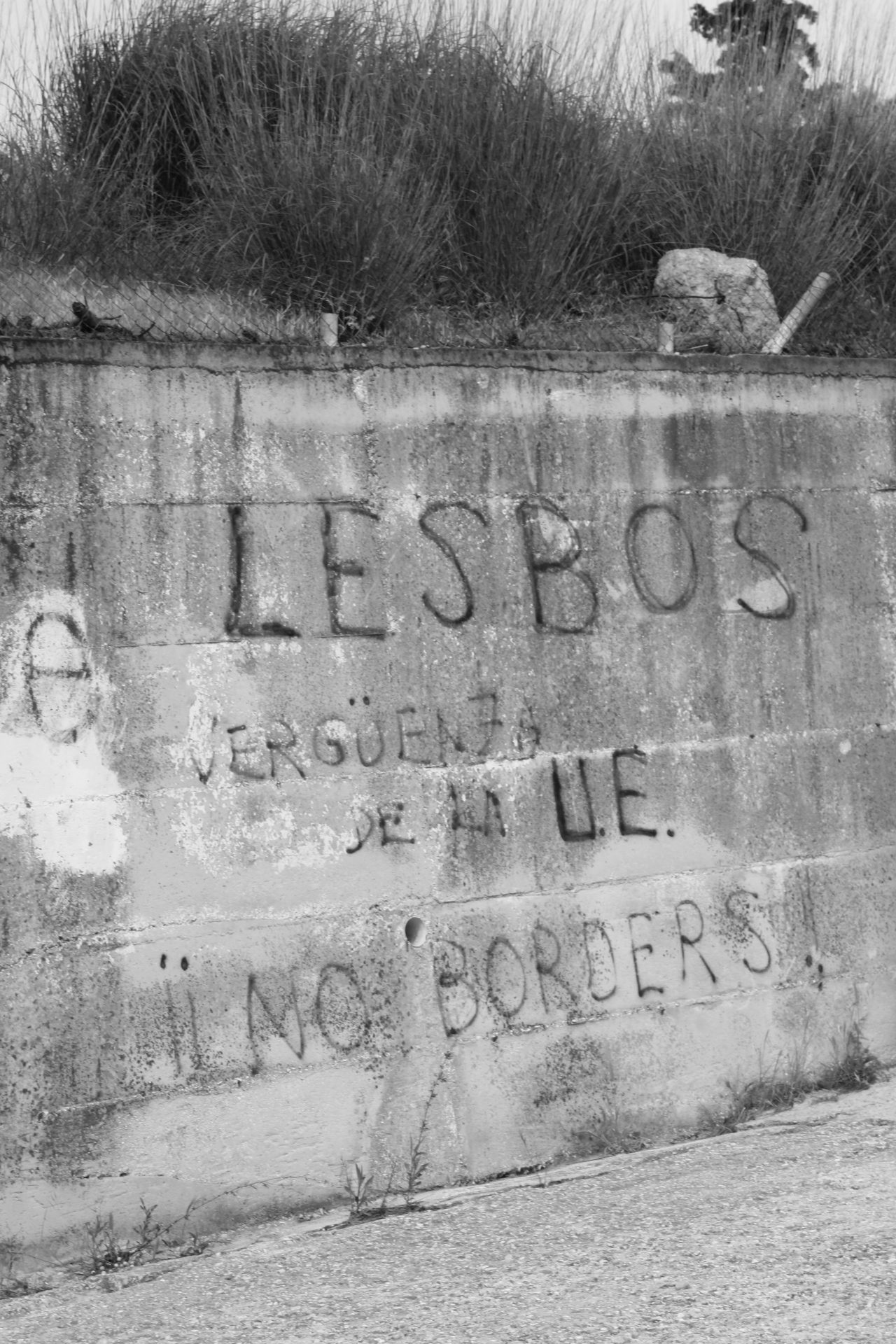

Ten years have passed since the refugee crisis of 2015, and the island of Lesbos has been and continues to be a symbol of this social and humanitarian situation. From the early years of discussions about solidarity with the war in Syria, to today, with Europe changing its stance and shifting to a strategy of deterrence.

Amina Namjogian, a woman who arrived on the island fleeing Iran with her child in her arms, remembers the grandmothers who fed foreign babies with bottles and the fishermen who saved lives at the risk of their own. Her arrival in Greece was followed by her stay at the Reception and Identification Center (RIC); she learned Greek and then emigrated to Germany, eventually returning to the island, where she now cooks Iranian dishes in a small restaurant, while her child, who is growing up with her, declares himself to be ‘Greek.’ The Lesbos that welcomed her back then bears little resemblance to today. The camps of that time, unorganised, dirt-floored and with tents, now resemble an Orwellian landscape where the camps are made of metal containers with cameras, barbed wire and guards. Europe no longer invites, it controls. And Greece, with its new legislation and threats of detention for rejected asylum seekers, is paving the way for a future of migration that is more punitive than protective (1);(5);(4).

Photo: Yorgos Karagiorgos / Kara Tepe-Mavrovouni, April 2024

The Mirror Island of Europe

In recent years, the European Union’s migration policy has shifted significantly from a fragmented, humanitarian approach to a strictly security-based and deterrent model. This change accelerated after the 2015 crisis, which exposed the weaknesses of the Common European Asylum System and fuelled the rise of xenophobic and far-right narratives. With increasing pressure from nationalist movements, even centrist governments adopted tougher rhetoric, leading to the adoption of the new Pact on Migration and Asylum in 2024. This pact aims to speed up border procedures, expand the use of closed structures, and impose a ‘solidarity’ mechanism, either through the relocation of asylum seekers or through financial compensation. However, critics argue that the emphasis on border control undermines the rights of refugees and may exacerbate human rights violations without effectively curbing migration flows (8), (9), (10).

At the same time, the EU has strengthened its strategy of externalising migration control to third countries of transit, offering financial and diplomatic incentives to prevent migrants from crossing before they reach European territory. Agreements with Libya, Turkey, Tunisia and other countries have effectively delegated the interception, detention and deportation of migrants to regimes or armed groups with a questionable human rights record. This externalisation has reinforced the creation of detention camps, the development of surveillance technologies and the militarisation of borders, increasingly involving private security and defence technology companies. Despite these investments, migration has not been substantially reduced, while the risks for migrants themselves have increased, reinforcing authoritarian practices in ‘partner’ countries. The overall shift in policy indicates a Europe that views human mobility as a threat rather than a complex challenge requiring a structural and long-term response (8), (9), (10).

During 2015–2016, more than one million refugees and migrants passed through Greece, half of them via Lesbos. Images of boats filled with people wearing orange life jackets covering the beach and residents distributing food and water marked the collective memory and were seen around the world. People such as Stratos Valamios, a fisherman by profession, became symbols when they rescued drowning children, while at the same time holding in their arms the bodies of people who could not be saved. The walls of taverns are still covered with thank-you cards, but something has changed (1).

The spirit of the residents now oscillates between disappointment and open opposition to whatever may come. Of course, this change did not come suddenly. The Moria Reception and Identification Centre, known for its overcrowding, lack of basic infrastructure and constant fires, was completely destroyed by fire in 2020. This was followed by the temporary camp at Kara Tepe, which was also characterised by shortcomings, although it was clearly more organised. Replacing these is now the “final solution”, which envisages a strategically isolated, fully controlled, EU-funded centre that seeks not to welcome, but to manage, monitor and discourage (1); (2); (6).

In a deserted area with pine and olive trees, one of the largest European reception centres is being set up: the Closed Controlled Access Centre of Vastra. This new camp, capable of accommodating up to 5,000 people, is more reminiscent of a prison than a reception centre. The project is almost complete, but remains closed pending a decision by the Council of State, following appeals by residents, environmental organisations and local authorities, who allege violations of legislation and a high risk of fire. Lesbos is becoming the testing ground for new European policies (1); (2);(7).

During 2015–2016, more than one million refugees and migrants passed through Greece, half of them via Lesbos. Images of boats filled with people wearing orange life jackets covering the beach and residents distributing food and water marked the collective memory and were seen around the world. People such as Stratos Valamios, a fisherman by profession, became symbols when they rescued drowning children, while at the same time holding in their arms the bodies of people who could not be saved. The walls of taverns are still covered with thank-you cards, but something has changed (1).

The spirit of the residents now oscillates between disappointment and open opposition to whatever may come. Of course, this change did not come suddenly. The Moria Reception and Identification Centre, known for its overcrowding, lack of basic infrastructure and constant fires, was completely destroyed by fire in 2020. This was followed by the temporary camp at Kara Tepe, which was also characterised by shortcomings, although it was clearly more organised. Replacing these is now the “final solution”, which envisages a strategically isolated, fully controlled, EU-funded centre that seeks not to welcome, but to manage, monitor and discourage (1); (2); (6).

Photo: Michalis Bakas / Vastra’s Reception Center

In a deserted area with pine and olive trees, one of the largest European reception centres is being set up: the Closed Controlled Access Centre of Vastra. This new camp, capable of accommodating up to 5,000 people, is more reminiscent of a prison than a reception centre. The project is almost complete, but remains closed pending a decision by the Council of State, following appeals by residents, environmental organisations and local authorities, who allege violations of legislation and a high risk of fire. Lesbos is becoming the testing ground for new European policies (1); (2);(7).

Photo: Yorgos Karagiorgos / Moria, April 2024