Maritime affairs and marine parks

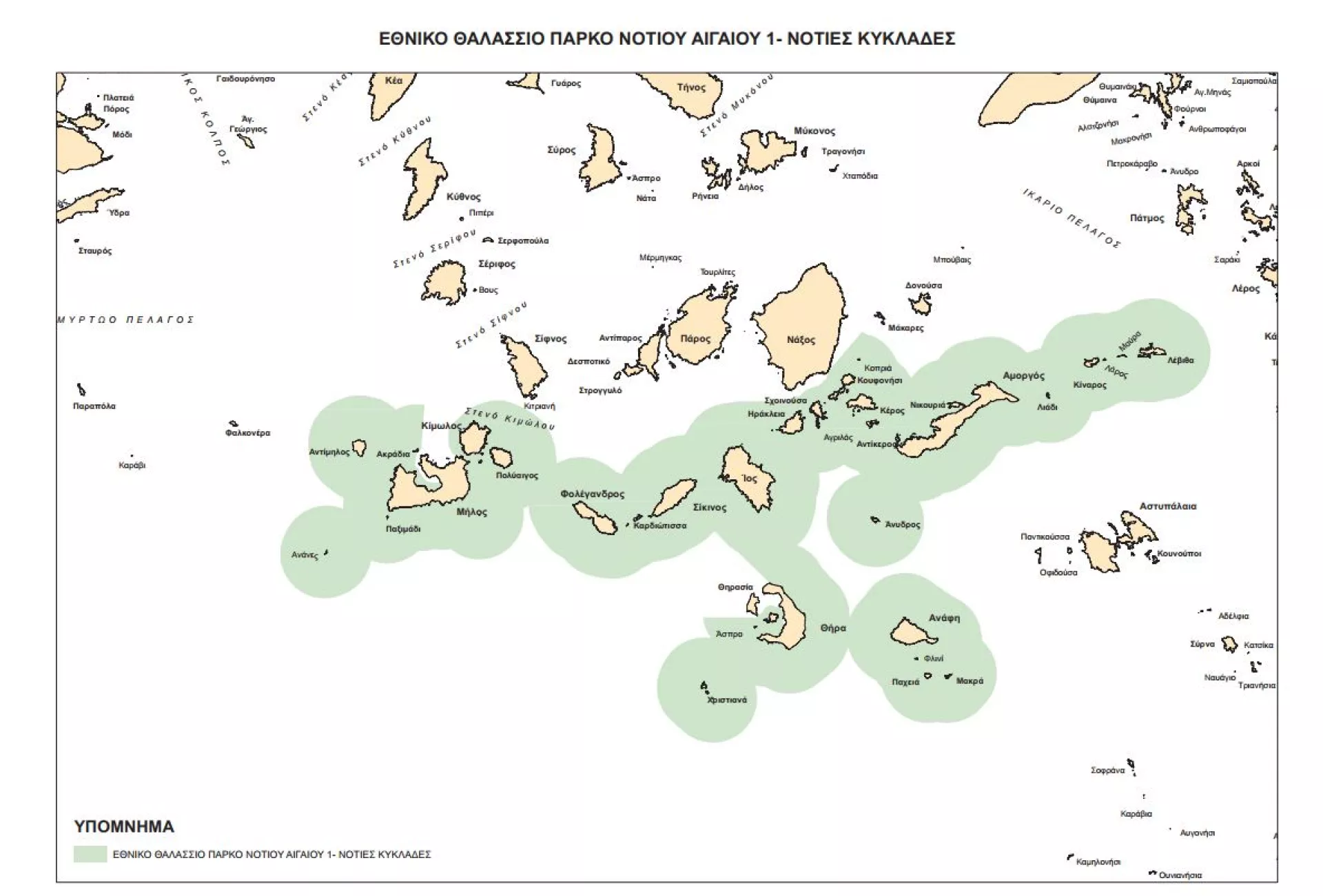

Greece and Turkey have almost simultaneously declared new marine parks, with environmental concerns serving as a geopolitical pretext. The Greek government announced the creation of two new national marine parks, one in the Ionian Sea and one in the southern Cyclades. This move was presented by Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis as a tribute to Greece’s maritime heritage. The park in the Ionian Sea covers approximately 18,000 square kilometers, while the one in the Cyclades covers approximately 9,500 square kilometers, with the aim of protecting 30% of Greek waters by 2030, thus fulfilling the commitments made at European Union level for the protection of the sea.

The areas included in Greece’s marine parks are home to rare marine species, such as the Mediterranean monk seal, sperm whales, and sea turtles, while 42 areas of the Natura 2000 network have also been included in the protected zones. The terms under which these parks were announced include a management plan that completely prohibits trawling and fishing with submersible gear, while only traditional forms of fishing, scientific research, and certain tourist activities under certain conditions. The same management plan stipulates that hydrocarbon extraction (process of removing oil, natural gas, or other hydrocarbon compounds from underground reservoirs for energy production and industrial use) is prohibited within and around protected areas, with the government even including the concession area of Katakolo in the Ionian Park, sending a message that priority is given to the natural environment over energy projects. The management framework will be supported by a comprehensive monitoring system, using satellites, radar, and drones, according to the Natural Environment and Climate Change Authority.

The ecological footprint of these initiatives is, of course, clear and stated—what is not immediately stated is that, Greece, through these kinds of moves, is indirectly challenging the Turkish–Libyan memorandum (The Turkish–Libyan memorandum is a 2019 maritime deal between Turkey and Libya’s GNA, defining exclusive economic zones in the Eastern Mediterranean, contested by Greece and others) and, on the other hand, is declaring its effective maritime sovereignty through environmental policy.

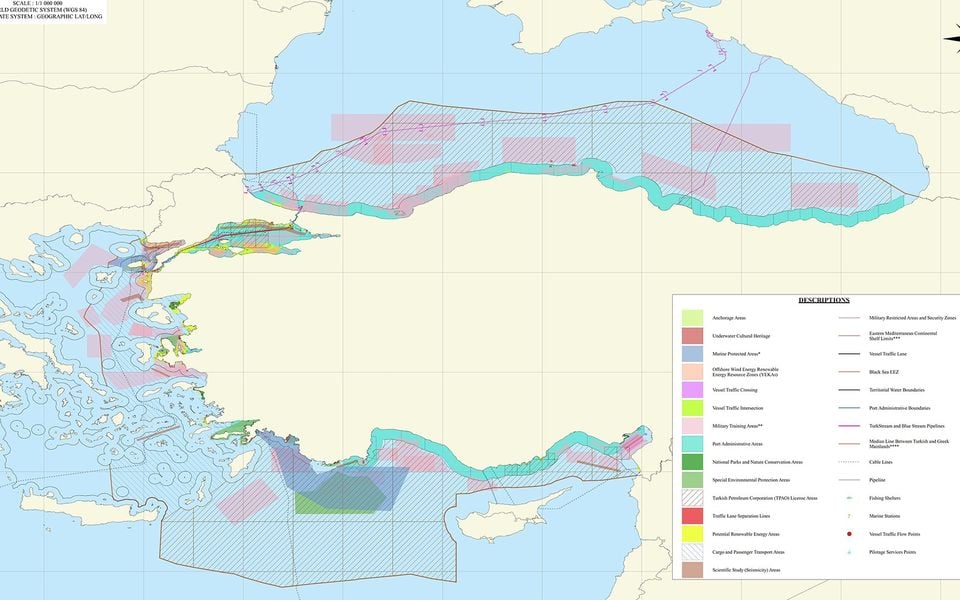

A few weeks later, Turkey submitted maps showing two of its own marine protected areas, one in the Aegean Sea and the other off the Mediterranean coast, sparking a strong reaction from Greek diplomats. These areas were presented by the Turkish authorities as “zones of absolute environmental protection,” with the aim, as stated, of protecting the marine ecosystem without hindering navigation or commercial activity.

The area chosen by Ankara extends west of Imbros and Tenedos, and even between Samothrace and Lemnos, i.e. in maritime areas without a defined continental shelf, as pointed out by the Greek Foreign Ministry, which described the Turkish announcements as “unilateral and illegal.”

Turkey’s announced marine parks extend west of the islands of Imbros (Gökçeada) and Tenedos (Bozcaada), while the second covers a large area in the eastern Mediterranean, starting northeast of Rhodes and reaching as far as the Gulf of Antalya, completely omitting the island of Kastellorizo. This was seen as a bit of a problem by Athens, since it ignores a Greek island that’s in the area.

Marine Spatial Planning of Türkiye. (Photo via DEHUKAM)

At the same time, Turkey included in its zones maritime areas extending beyond Turkish territorial waters, more specifically, it included in its maps the area between Lemnos and Samothrace, where no Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) or continental shelf has been demarcated. According to the Law of the Sea, a country does not have the right to unilaterally impose restrictions or protective measures in unmarked zones, something that the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs emphasized. However, the Turkish side, through its Ministry of Foreign Affairs, has made statements that Athens is “politicising environmental initiatives” in order to promote national claims in areas with an unclear legal status.

In essence, Greece interprets Turkey’s announcements as yet another attempt to create a fait accompli in the Aegean and the Eastern Mediterranean, where for decades the two countries have been at odds over issues of sovereignty, airspace, and maritime boundaries.