Why does history matter, especially for young people?

The obvious answer is that history helps us avoid repeating past mistakes, but for me it’s also about critical thinking. Someone who understands history will usually understand politics better than someone who only studies politics, because almost everything we see now has happened in some form before. The names change, the technologies change, but the behaviours and patterns are often similar.

For young people, history is the field that invites questions: the why, how, when, where. You walk down a street, look at a building and wonder what it looked like 50 years ago, what events took place there, how the city has changed. That curiosity then spills over into other areas, from philosophy to languages, and it gives you a deeper perspective on whatever is happening around you.

How did your social media presence begin?

It started during the pandemic. I had always liked looking at old photos and videos, but it was a private taste and I didn’t talk about it with my family. I was in several Facebook groups where people shared historical images, and I thought: maybe I’ll create a page and post things I find interesting; there must be people like me out there. I launched “Portugal Antigamente” (Portugal in the past, in English) spontaneously and began sharing photos, without any big intellectual plan. At first there was no proper source work, I didn’t even indicate which archive a picture came from.

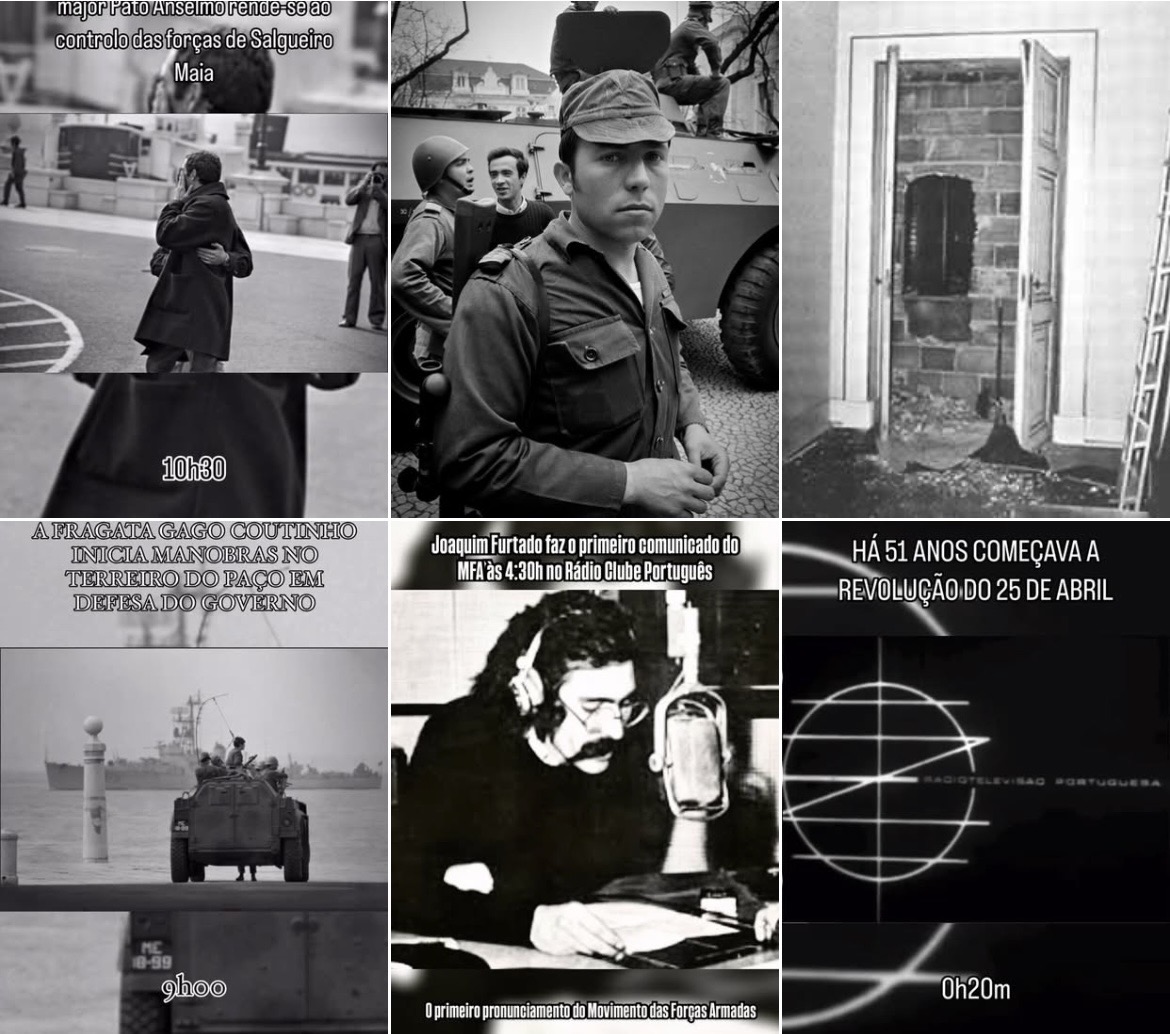

Over time the page grew, but the turning point came on 25 April’s celebration (Portugal’s Freedom Day) in 2024, when it went from around 8,000 followers to nearly 100,000 in a month. That was when I realised this was no longer a hobby and that it had become one of the most visible history pages in the country, which carried real public responsibility.

What does public responsibility mean in practice here?

We are dealing with a country’s history, which is politically divisive, so every image and caption can be read through different lenses. I began receiving messages from across the political spectrum, and I understood that what I posted could influence how people see the past.

As a historian, I don’t believe in total impartiality. We are shaped by our experiences, our readings, our context, and that inevitably affects interpretation. But we can still aim for rigour. Instead of relying on a single authoritative book, I try to read different historians; for example, on the Estado Novo period I will put interpretations from the right and the left side by side and then build my own synthesis. For me, the key skill is historiographical critique: knowing how to analyse sources and convey not just what others wrote, but what you have understood and tested against other work. My platform reflects my perspective, but it is grounded in a critical process rather than in nostalgia or party lines.