Music can be heard among the flat roofs dotted with rainwater canisters. It’s not a jukebox, which is often heard in the Favela Monte Azul, but someone practicing the violin. The music school – the Escola de Música – lends its instruments to students so they can continue practicing at home. Home is the Favela Monte Azul in the south of São Paulo, the largest city in Brazil and South America. Favela is the Brazilian term for slum – which initially brings to mind stagnant sewage and poverty. But anyone who visits Monte Azul will be surprised.

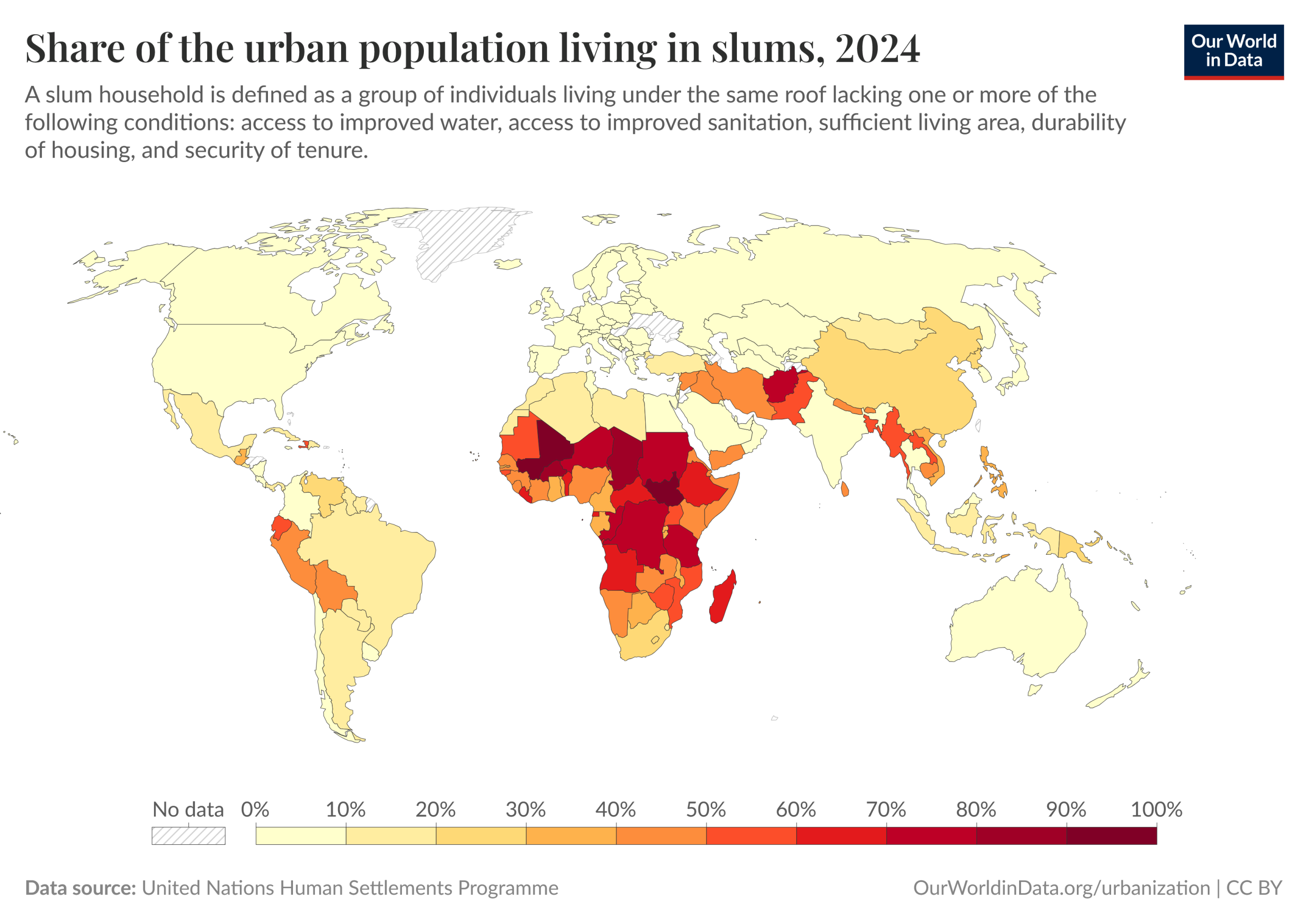

For Europeans in particular, the reality of a slum is a distant one. The UN-Habitat estimates that more than 1.12 billion people worldwide live in slums or informal settlements. However, if you look at the maps to Europe, North America and Australia, the proportion of the urban population living in slums is between 0 and 0.1 percent, according to the NGO Our World in Data. The ‘Western world’ not only has little experience with the challenges and potential of irregular settlements, but is also equally responsible for them on a global scale.

But the first step is to learn more about irregular settlements. This summer, I visited the Favela Monte Azul in São Paulo. Let me take you there.

Interactive Map here

Inside Out — How do irregular settlements come about, and what characterizes them?

When we arrive for the interview, Mário is sitting on the sofa in his office at the Centro Cultural, tuning a guitar for one of the children. Like the Escola de Música, the Centro Cultural belongs to the Associação Comunitária Monte Azul. The Associação also runs a Waldorf school, a birthing centre and workshops, provides basic medical care, offers career guidance courses and much more. It has more than 220 employees and is active not only in Monte Azul, but also in other favelas in São Paulo. It is managed by a small group of coordinators, Mário being one of them.

- In 1984, the spring was tapped and the wastewater could be diverted.

- The sewage flow was covered with a layer of concrete.

When the Associação was founded in the 1980s, Monte Azul looked very different from how it does now. The houses were dilapidated and there was no connection to the state electricity and sewage networks. During the rainy season, the paths turned into muddy corridors and rubbish was everywhere. Today, things look different, even though the favela with its self-built houses and unpaved paths still exists. There are shops, restaurants, a music school and childcare facilities. The houses are more stable, have several floors and are supplied with electricity and hot water. Although there is drug trafficking, it is governed by a strict code of conduct – for example, children must be kept out of the loop. There are no weapons to be seen, nor does anyone feel unsafe. The houses are decorated with colourful graffiti and mosaics. When sunlight falls on the favela, it glows.

Irregular settlements, which actually include the Monte Azul favela, are a product of rapid urbanization – the trend towards more and more people living in cities worldwide. When the influx is too great, the state can no longer keep up with housing construction. As a result, people build their own houses on the outskirts of cities, against the law and without the support or planning of the state. A distinguishing feature of irregular settlements is the absence of the state – for example, they are not connected to state infrastructure such as transport, electricity, water, sewage, waste collection or an address system. The streets are too narrow for cars and often steep, the houses are self-built and not very stable. There are no social infrastructures such as kindergartens, schools, parks, or shops. Irregular settlements are always characterized by the poverty of their inhabitants – as well as by more scope for crime.

But Monte Azul is different today. Of course, it is not the quiet terraced housing estate familiar in Europe. It is not even comparable to life in the numerous high-rise buildings of São Paulo, which the city administration rapidly built to provide more living space. The houses in the favela are poorly insulated against noise and heat, and there are still occasional problems with rubbish. But against many prejudices, there are no personal safety issues when it comes to one’s own favela. People look out for each other, and there is a sense of community that is unique even for Brazil.

Street next to the Monte Azul favela, with the skyscrapers of São Paulo in the background.

Glance at the world — How do irregular settlements differ around the world?

While in Brazil irregular settlements are called ‘favelas’, in Ecuador they are called “invasiones” and in Peru ‘barraidas’. They are similar throughout South and Central America, albeit with different names. This is partly because many countries in this region share a similar colonial past and experiences with military dictatorships. South and Central America are home to some of the most dangerous regions in the world – and informal settlements in particular are associated with organized crime, drug trafficking and violence. But the assumption that crime only happens there or that the residents are inevitably criminals is wrong – on the contrary, they themselves suffer from violence and drug trafficking. In this region, it is particularly clear to see the influence that existing power structures can have on the success of a project.

There are very different types of irregular settlements in the Indo-Pacific region. China, with its rapid population growth between 1950 and 1970 that continued in the following years and strong urbanization over the last forty years, should have particularly pronounced slums. However, the opposite is true – at least officially. To understand China’s special position, one must look at the institutional framework of housing and urbanization policy. The official residence control system in China (Hukou system/戶口制度) prevents people from leaving their place of origin, where they no longer have access to social services such as education or health insurance. Then as now, the aim is to prevent too many people in the cities from causing the social systems there to collapse. ‘China is not free of slums, just not in the cities, but institutionalized in the countryside,’ explained Jiayan Zhang of Minzu University (Chengdu) in 2021. In fact, this system has led to stark differences between citizens of rural and urban regions in China.

To prevent irregular urbanization, China is focusing on heavily state-subsidised housing construction on the one hand and, on the other, taking repressive measures against emerging settlements through demolition and resettlement. In some (regional) areas, the hukou system has now been reformed and slightly opened up – however, inequality of opportunity remains in many areas, as priority is given to employment status and social security. What remains are huge settlements, often on the outskirts of cities, consisting mainly of social housing. This means they are state-owned and do not fall into the ‘slum’ category. However, these neighbourhoods are typically of poor construction quality, have poor connections to the city’s infrastructure, and their ‘transitional’ nature results in capsule or cage flats. They are mainly home to workers who come from the countryside, have no access to social services in the city and are completely dependent on their employment contracts. Schematically, these neighbourhoods do not fall into the same category as slums in South America or Africa, but they are characterized by the same features – above all, the absence of the state.

India is also known for its large population. In 2023, around 63.6 per cent of the population lived in rural areas. However, of the population living in cities in 2022, 42.45 per cent live in irregular settlements. Values between 50 and 60 per cent can be found in Pakistan, Myanmar and Bangladesh, for example. Pakistan is also home to the world’s largest slum in terms of area and population: Orangi Town in Karachi. In international comparison, slums in this region are particularly vulnerable to natural disasters – especially as extreme weather events are increasing due to the progression of climate change. An Indonesian study concluded that the poor population suffers most from these events and that their precarious living conditions – in addition to the danger of dying in collapsing houses – can be exacerbated life-threatening. For example, through a lack of access to drinking water. They are ‘dependent on their own creativity to survive’.

Similar to other regions, slums often provide accommodation for workers in the low-wage sector, who have become an integral part of global economic chains, supplying highly industrialized countries with cheap products. One example of this is the textile factories in Dhaka, Bangladesh. The location of the factories and slums is closely intertwined. For many workers, living in the slums is the only option, as there are no state-run social housing projects for those on low incomes.

2022, some more than 53.6 per cent of people lived in informal settlements worldwide on the African continent – even though the continent accounts for only around 17.8 per cent of the total world population. Africa is the continent with the strongest population growth – at the same time, countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo and Sudan are ravaged by civil wars. These not only destabilize or destroy the state structures necessary for fair housing policies, but also lead to displacement and economic instability. The latter contribute significantly to migration to cities. In addition, large African cities – such as Nairobi in Kenya and Dar es Salaam in Tanzania – still have relics from the colonial era. At that time, they were structurally designed to segregate society according to skin colour, social status and income. Infrastructure dating back to the colonial era is designed to exploit the country’s resources rather than to serve a city and its people. This makes it all the more difficult for urban planners to break down these structures.

For highly industrialized countries such as the USA or European countries, slums seem to be something for ‘the rest of the world’; irregular settlements are more likely to be referred to as informal camps or homeless camps. It is true that there are no irregular settlements here that can compete in terms of size. This is mainly because there are usually legal regulatory mechanisms and a strong social system in place that can dismantle illegal camps or take preventive action against them.

However, the term originally comes from Great Britain, where during industrialization, ‘working-class/poor neighbourhoods’ formed near factories, which grew unnaturally quickly and offered people little infrastructure. But even in the more recent past, large irregular settlements have emerged, such as the ‘Gecekondu’ in Turkey, which have contributed significantly to population growth around the country’s major cities. Nevertheless, the ‘deprived neighbourhoods’ that exist in the global North cannot be compared to irregular settlements or slums in the rest of the world – they do not meet the necessary criteria and would glorify the situation in real slums.

Approaches to solutions – From Survival to creativity

On the one hand, informal settlements are unique around the world, influenced by location, political approaches and the history of the country. That is why every urbanization and improvement project should be tailored individually to the obstacles and needs of the residents. On the other hand, there are characteristics that informal settlements around the world have in common. That is why it is possible to constantly recombine solutions from a global pool of approaches.

Local improvement and upgrading projects often require little political action, as they are carried out by NGOs and aid organizations. They have the potential to directly improve people’s living conditions, for example by stabilizing a roof. This is particularly useful as emergency aid, e.g. after a natural disaster. Improvements to infrastructure, on the other hand, are only possible in cooperation with the state or city. However, long-term change in living conditions must also be based on poverty reduction and education. In addition, complications can arise when outsiders intervene in the social dynamics of the settlement at such short notice – it is only natural that they are not always trusted.

Social projects can be particularly helpful in this regard. These projects are not focused on physically improving the living environment, but rather on social infrastructure – for example, through kindergartens or the provision of further education. The aim is to relieve the burden on residents and provide them with further training in order to help them find a way out of poverty. It is important that these projects are designed for the long term and are carried out in line with the needs of the residents. Another approach is to combat stigmatization outside informal settlements rather than within them. One obstacle for people from informal settlements is social perception, which prevents them from improving their situation. This stigmatization has the potential to become a self-fulfilling prophecy. With this approach, too, it is essential that an organization makes a long-term commitment.

Another solution, which can only be implemented in cooperation with the government, is to grant land rights to residents. This would formally legalize the dwellings, protect people from involuntary resettlement, and enhance their social status. It is also expected to increase the value of the dwellings, as people would be able to start investing in them privately. Although this approach is undoubtedly desirable – also for overall destigmatization – it does not necessarily always lead to an improvement in living conditions. People make investments when they feel secure – but this also depends on their trust in the state and legal system, as well as the general security situation. However, if this trust has been destroyed – as is often the case with people who have been affected by poverty (for generations) or have experienced war – formal recognition does not always bring about the desired improvement in living conditions. Microloans or start-up capital can also be granted to stimulate private and local investment – for example, to promote social infrastructure such as restaurants or shops in the settlement.

At this point, we can return to the Associação Comunitária Monte Azul as a positive example. The organization is not a European initiative, even though many of its volunteers come from Europe – it actually employs Brazilians, mainly people from the favela itself. It is not only an employer and childcare provider, but also a social circle and political voice. It knows exactly what people need, not through surveys, but by empowering people themselves to bring about the changes they want to see. That may sound idealistic, but it works. Through long-term, close cooperation, the Associação has become an integral part of the favela and has transformed it into a place where people enjoy living. Its work can serve as a model for the urbanization of informal settlements worldwide.

View over the Monte Azul favela in the sunshine.

In general, however, it can be said that the state plays a decisive role in dealing with irregular settlements. Firstly, by expanding the infrastructure in existing settlements. The key word here is ‘participatory planning’ – with citizen participation, the needs of the residents are not overlooked. Secondly, by accommodating immigrants with social housing. This can prevent irregular settlements from arising in the first place. And thirdly, by making life in rural areas more attractive. Even if urbanization continues, it is possible to prevent social systems and housing construction in cities from becoming overburdened – by slowing down urbanization. This involves, for example, supporting local production and protecting it from mass production, expanding rural (social) infrastructure and equalizing income levels.

Since tackling the structural problems of an irregular settlement – lack of infrastructure, poverty, crime, etc. – is almost exclusively the responsibility of the respective state, it is important to realize that initiatives or NGOs can only have a limited impact. Even if they are often unable to bring about structural change, they can still improve people’s living conditions in the long term. No single measure is complete on its own – for a project to be successful, they must complement each other.

What role does Europe play?

Europe has a clear shared responsibility for improving living conditions in irregular settlements worldwide – in a hyper-globalised world in times of climate crisis, it is outdated to view issues within national borders, or even world regions. Furthermore, Europe still has a colonial legacy and a responsibility to share the innovations of its own economic power.

At the same time, it should be clear that Europe cannot present ‘the best’ solution to this issue – simply because the problem is largely non-existent in Europe. Instead, there are many organizations in the countries that have been developing tailor-made solutions for specific irregular settlements for years. What Europe can do to help is to continue to focus on development cooperation and not follow the example of the USA. One approach of the European Union, that can be viewed positively, is the network Capacitiy4Dev, where professionals from all over the world can connect and share their knowledge and resources. Europe can also take on an advisory role in structural issues such as the fight against corruption. Recognizing that other countries have difficulties that are unknown in Europe, and developing an understanding of this, could greatly facilitate cooperation in general.

The first step has already been taken – recognizing that an estimated 1.12 billion people worldwide live in these settlements. And not marginalizing them, but seeing their enormous potential.

Thanks goes to:

everyone from Monte Azul, Tarsila Riberio and Saskia Reimann

photos:

Magret Wedling or Associação Comunitária Monte Azul

Written by

Shape the conversation

Do you have anything to add to this story? Any ideas for interviews or angles we should explore? Let us know if you’d like to write a follow-up, a counterpoint, or share a similar story.